From the earliest civilizations onwards people have been drawing the world around them on stones, clay tablets, papyrus, and more. The way people see the world can tell future generations so much about the culture, perspectives, physical geography and other insights into the lives of those who have come before.

The evolution of the Western world is generally considered to have started in Greece, and with it, the foundations for modern cartography were born. Cartographers throughout history built upon the knowledge and work of the individuals before them creating continuity and understanding of the world along the way. The Renaissance in Europe marked the period coming out of the Dark Ages as art, music, literature, and society flourished with new knowledge. In this period advances in the art of mapmaking were made which have influenced modern geography and cartography as we know them today.

There are a few different types of medieval European Maps that have provided us with clues as to how early cartographers saw and mapped with world around them. As technology increased allowing explorers to discover parts of the world previously unknown to them, the boundaries of mapmaking were pushed farther and farther into the horizon. Additionally the increasing interactions between cultures of the world allowed for a pooling of resources and the knowledge to put together more complete maps of the Earth.

There are some common types of European Maps that were created in the medieval times and copied for generations afterwards. These types of maps include T-O maps, Zonal or Macrobian maps, Quadripartite maps and complex maps.

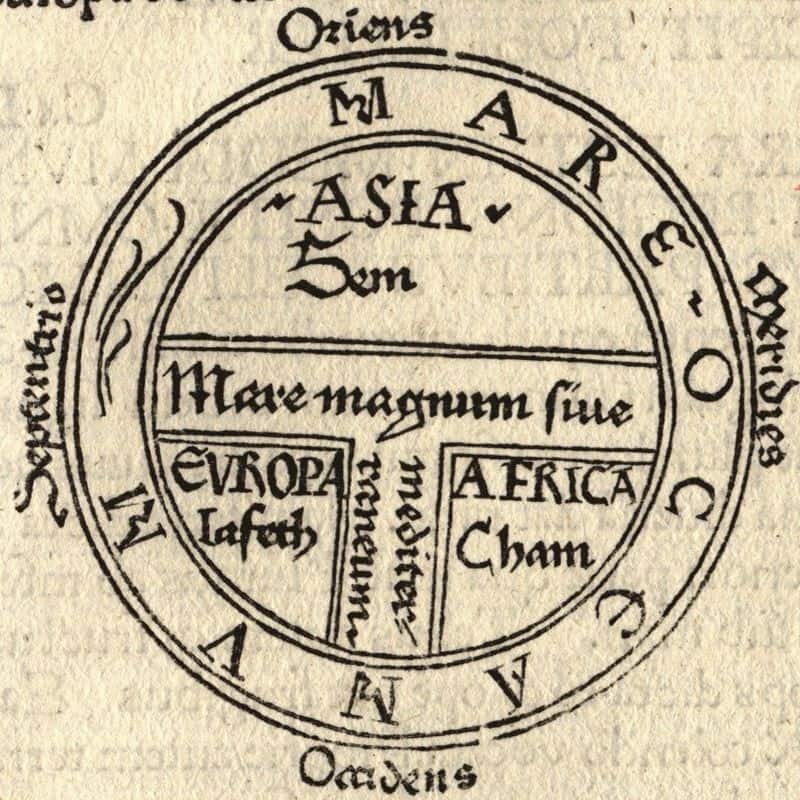

T-O Maps

T-O maps depict the world in three zones, the only known landmasses of the time. The map is oriented with east at the top of the map and a circle surrounding the known landforms of Asia, Africa and Europe forming a ‘T’ shape. The waters in between each section represent the Red Sea, the Black Sea, the Don River and the Sea of Azov. Scholars of these maps have come to understand that medieval scholars likely knew the earth was spherical, contradicting the common myth that Columbus was the first navigator to prove the Earth was round.

Zonal or Macrobian Maps

Zonal maps depict the climate of the Earth as it was understood by early cartographers. Zonal maps, as the name suggests, were divided up into five horizontal zones showing the different climates on Earth; only three of these zones, including populated Europe, were thought to be habitable at that time. Zonal maps are often referred to as Macrobian maps because most surviving examples of this type of medieval map are from Macrobius’ Commentary on Cicero’s Dream of Scipio.

Quadripartite Maps

Thirdly, the Quadripartite maps showed a kind of evolution of the T and O maps and the Zonal maps by depicting the three landforms of Asia, Africa and Europe separated from each other by water and separate from another unknown landform called Antipodes. Antipodes correlates with the inhabitable climate zones seen in Zonal maps, and also reflects the religious idea that no people could be living outside of the Christian realm. The relics of Quadripartite maps show the increasing understanding of Europeans that there might be unexplored lands in the world that they had not previously taken into consideration when drawing their maps.

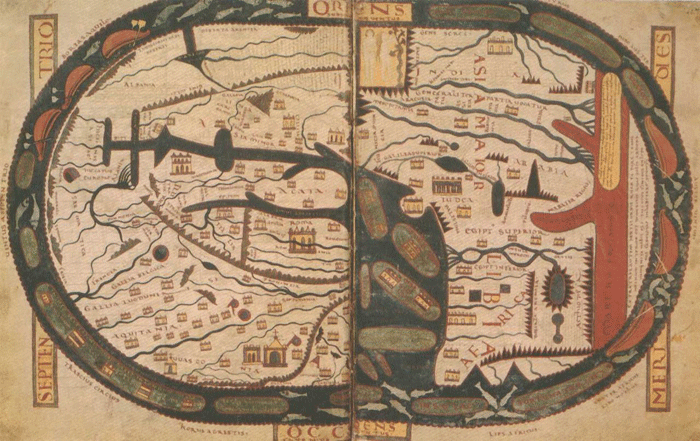

Complex Maps

Finally, the complex maps of Medieval Europe were much more detailed and larger than their counterparts, although still not very accurate according to modern standards. Complex maps detailed cities, rivers, landforms, mountain ranges, and more physical geography details in addition to documenting local and exotic flora and fauna gleaned from texts passed down from the Greeks and Romans.

Many complex maps still remain, the largest existing specimen called the Hereford Map which is 1.5 meters across. These were the basis on which an understanding of the world to many Europeans was created.

Known as mappae mundi, Medieval European maps were used to show the world around the Europeans as they knew it. They mapped the world in relation to their towns, their regions, the stars and their faiths. They may not have had satellite imagery or the ability to chart unknown territories, but their cartographic advances made it possible for modern day cartographers and geologists to have these skills.

As the art of cartography progressed during the Middle Ages mappae mundi began to change to show an increasing understanding of the oceans and life beyond the Mediterranean Sea. These maps, called Portolan charts, eventually began to modernize mapmaking beyond the classic mappae mundi.

So, although mappae mundi were not the peak of cartographic excellence, they aren’t meant to be. The things shown in these maps bring great insight into the times they were created and give us a valuable perspective into what live was like during the Middle Ages in Europe.

References

Wikipedia. Mappa Mundi. 2014. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mappa_mundi

Livingston, Michael. Strange Horizons. Modern Medieval Map Myths: The Flat World, Ancient Sea-Kings, and Dragons. 10 June 2002. http://www.strangehorizons.com/2002/20020610/medieval_maps.shtml

Hereford Cathedral. Mappa Mundi. 2014. http://www.themappamundi.co.uk/

BBC. A History of the World. Mappa Mundi. 2014. http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/zrKd-Z0wS7CSYjB_DlRbrA