Recent research has shown that one of Greeland’s largest glaciers is losing up to five billion tons of ice every year as it melts into the ocean. Ice sheets worldwide are disappearing as global warming and climate change take their toll.

Coastlines and low lying nations have the most to lose should the world’s glaciers melt completely; some would be entirely engulfed by water as sea levels rise.

Greenland’s Zachariae Isstrom glacier

Greenland’s Zachariae Isstrom glacier, located in the northeast part of the country, could raise sea levels by 46cm if it melted completely away.

Scientists are taking a closer look at the glacier as satellite imagery and other research devices have made it easier to track the changes in glaciers.

The last few years have seen many changes in Zachariae Isstrom’s form and shape, including how fast the ice is melting and how quickly other ice is adding to the glacier. The glacier has been calving icebergs into the ocean around it at an increasing rate.

Ice located in the polar regions of the Earth is the most watched as they are indicators of how much climate change is affecting Earth’s natural processes.

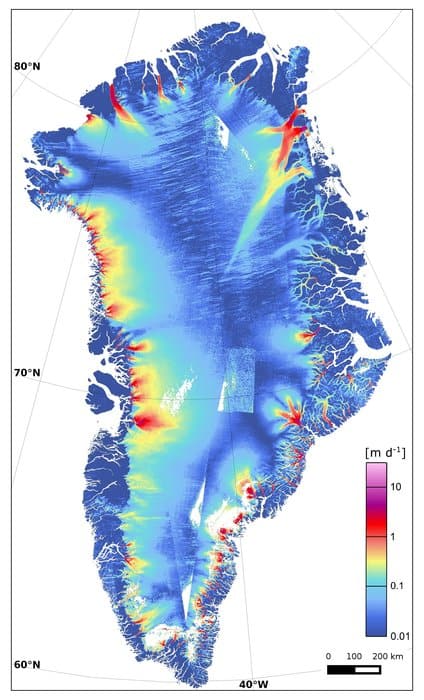

Radar and satellite technologies from Japan, Italy, Canada, and Germany have all compiled their data on the world’s ice sheets to determine just where things are changing the quickest. Glaciers grow and change as the Earth changes; anything from air temperature increases to changes in ocean temperature affect how a glacier forms or breaks down.

Using radar data to track glacier melt

The Polar Space Task Group is just one international organization working with climate agencies and governments globally to track efforts related to ice cap research. They focus on Greenland and Antarctica, but have interests in glaciers located in other regions as well.

Nearly a decade of radar data has also been put to use to determine some of the factors that are contributing to the rapid decrease of Zaccariae Isstrom. Scientists think that the warmer ocean temperatures have eroded the base of the Greenland glacier, contributing to the meltwater already coming off of its surface.

Regular monitoring of the glacier is essential for understanding how the climate effects affect Earth’s ice sheets. The Copernicus Sentinel-1A satellite recently came online and will help the Polar Space Task Group monitor the glacier constantly. Using satellite, radar, and other measurements, scientists can track the glacier for up to date information on how climate change is influencing the growth and decline of important ice sheets on Earth.

More: International Effort Reveals Greenland Ice Loss – European Space Agency, November 13, 2015.