The essence of science fiction — whether in print or on the screen — is its imagining of our future. This, and not the plot or the characters, is what keeps the reader, or the viewer, fixed to the story. Could it be? we ask ourselves, in wonder or in dread. The same holds for actual science writing about the future, both popular and learned. Ever since we humans came to realize, during the Industrial Revolution in the nineteenth century, that the future would no longer simply be a repetition of the past because science and technology were having irreversible effects on how we live our lives, our scientists have promised ever greater marvels while our writers have projected dehumanized dystopias where things have gone terribly wrong. In the 1950s, as computers were increasingly used to predict the future by crunching the numbers thrown up by extrapolations from social and economic trends, all such predictive efforts were gathered under the rubric of ‘futurology,’ and this book covers them all.

The author, a professor emeritus of the history of science from Queen’s University in Belfast, Northern Ireland, spent his career researching the history of Darwinism, producing a goodly number of books, both original and surveys, on biology and closely related subjects. He explains his transition to his current book by noting that the debate over Darwinism was, from the outset, closely linked both to the idea of progress and to the whole question of science and religion. A logical step, then, to a book-length survey of the history of futuristic predictions from the nineteenth century on through the first two-thirds of the twentieth, in the English-speaking world. The book is also by way of a swan song.

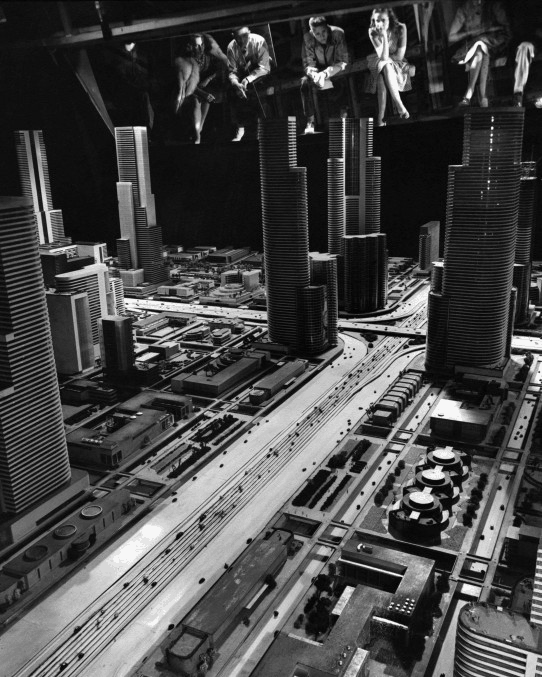

The book’s chapters each cover a practical category of our daily lives, such as the home, communications, travel, the environment, space, and war. Each combines a succinct account of the actual scientific and technological advances in its category, with a quick look — somewhat hit-or-miss — at how these advances were either predicted or not in both popular science writing and in science fiction. Urban noise and pollution abatement, for instance, was addressed by H.G. Wells in an early story which depicted a world in which everybody lived in apartments within huge cities enclosed in transparent roofs; in this world, Britain had but four such mega-cities while the rest of the land was used for mechanized agriculture. In 1925, Commonweal, a Catholic magazine, complained that such super-cities would produce a dehumanized society with no community or soul. Rather more practical, the New York World’s Fair of 1939 featured several exhibitions envisioning the future city with brighter faces, all stemming from the ideas of such contemporary architects as Frank Lloyd Wright or Le Corbusier. While the emphasis was on efficiency, these were cities built for actual humans to live in.

It would seem that the more scientific training the one imagining the future has, the more positive the outcome of the imagination. Certainly, there was such a distinct dichotomy in attitude readily apparent in popular writers. Popular science writers, who published in magazines like Popular Mechanics, were invariably optimistic in outlook, concentrating on the practical applications and benefits of scientific and technological advances (the better mouse-trap syndrome), while science fiction writers tended towards the dark side.

H.G. Wells, at the turn of the century, was the first major writer to make the development of science and its industrial applications central to any projection of social transformation — the practical social prophet had to understand how such technologies were actually changing and ameliorating the burdens of daily life. Wells was a social campaigner seeking to reform society along lines that would make the future better for all; he was also a visionary who understood and feared that new weapons such as aircraft would make war far more destructive. His popular novels, such as When the Sleeper Awakes, tended to emphasize the worsening effects of gigantism, everything from apartment buildings to cities to war just getting larger and more dehumanizing. George Orwell also depicted, as Wells had, a future society based on extrapolations from current interactions of science and technology with social and cultural values; and, in a historical period when our progressives looked to the Soviet Union as the future, the result was 1984. This truly was a dehumanized world where regimes used technology to control every aspect of life.

But, as in Nevil Shute’s heartrending On the Beach, the technology of 1984 was simply the technology of the time. True science fiction, as defined by Isaac Asimov, imagined new technologies, transformative not extrapolated; and it placed its heroes in situations defined by the problems created by these technologies. Asimov pointed as particularly illustrative of this definition to the early stories of Robert A. Heinlein, which already in 1941 depicted a world where men struggled with the political and moral challenges of nuclear weapons. Heinlein himself preferred the term ‘speculative fiction,’ which serves to highlight perhaps the major contribution which our science fiction writers make to society in general (beyond, that is, the pleasure they give their readers) — the inspiration they give to scientists and to those who fund them to actually create the technologies they imagine in their stories. Thus, at a time when corporations like IBM were built on the assumption that computers were large-scale machines (occupying entire buildings), suitable solely for use by government and big business, when, that is, no one was imagining the PC (because the transistor had not yet been invented), Asimov was writing stories about human-sized robots with a ‘positronic brain’ inside their skulls.

With a bibliography of some 20 pages, this is a serious and thorough look at the sometimes beneficial, sometimes baleful inter-play of our scientists and the writers who both mimic them and inspire them. Without servious cavil, daily life in our world has been made so measurably better by our scientists and our inventors. By bringing to the fore the monitory imaginings of our science fiction writers, Professor Bowler provides us with a guidebook to how our dreams can become nightmares.

A review copy of this book was received.

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Disclosure Statement”]Geo Lounge is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to amazon.com. Amazon, the Amazon logo, AmazonSupply, and the AmazonSupply logo are trademarks of Amazon.com, Inc. or its affiliates.[/toggle]

[/accordion]

Peter J. Bowler A History of the Future: Prophets of Progress from H.G. Wells to Isaac Asimov (Cambridge University Press, 2017), Ppk x, 286 ISBN: 9781316602621