Some technological advances redefine an industry, while others merely push the boundaries. In mapping, technology historically divides the field, but tomorrow’s advances might be able to reunite it. The maps of the future will be automatically created and updated, holding information as well as history.

Maps are like the people who make them: they have different specialties and different faces. A map could be as simple as a record of a journey; x marks the spot and each dash is a step. A topographical map, on the other hand, edges into the territory of data visualization, while still recording a terrain that may well change with erosion and other geological factors. Google Maps pushes mapping into the realm of data storage and retrieval. Digital maps still store instructions for travel, but in the form of arrival times and freeway exit numbers.

The common element is that mapping is about documentation, and using that documentation to understand and interact with the world. The future of mapping combines the domains of records, data visualization, and data storage and retrieval. The next generation of maps will leverage advances in machine vision, as well as the power and investment of individual citizens roaming the world, to create a single source of GIS information.

The New Cartographers

In the begining, mapping technology was a pencil and paper and the cartographer’s eyes. But measuring with string turned into measuring with lasers, and now mapping is more and more automated.

Thus the computer becomes the cartographer. But how does it see the world? As self-driving cars are positioned to become huge consumers of maps, the cars themselves will record their journeys. But those maps will likely remain proprietary to the car manufacturers, as already reflected in Tesla and Uber’s acquisitions of mapping startups.

The challenge of the future is to get a virtual world into the cloud. Mapillary, a Swedish startup founded in 2013, has been putting it there with the help of tens of thousands of worldwide users.

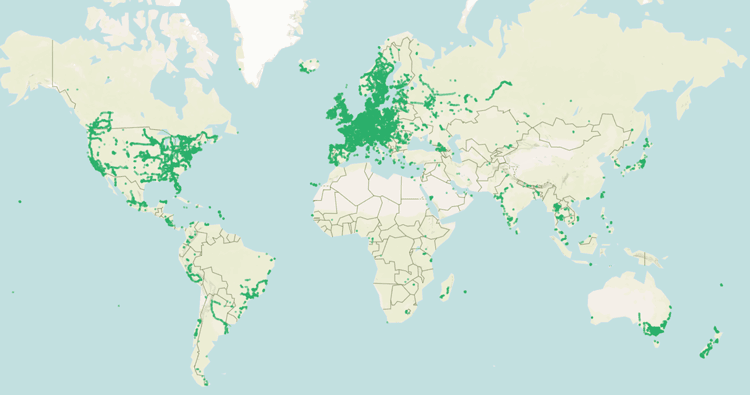

Mapillary is an app, but it’s also a community. Using mobile phones, 360-degree cameras, car dashboards and helmet cameras, Mapillary’s users take geo-tagged pictures of the roads they travel which the app automatically uploads to Mapillary’s platform. Then, Mapillary stitches the photos together and turns them into an immersive, navigable, street level view of the world. The community has mapped over a million kilometers with over 40 million pictures.

Crucially, Mapillary’s crowdsourced maps cover areas that Google Street View doesn’t see. Germany for instance has broader coverage on Mapillary than Google, which was waylaid by privacy suits. Mapillary’s community doesn’t only stick to population centers, but follows the paths of the people who use it. When the Red Cross needs to record the streets in Haiti, Mapillary is their platform. As the city of Dar Es Salaam works with the World Bank to mitigate the danger of flash flooding, Mapillary helps document at-risk areas.

In this sense, Mapillary engages with the traditional philosophy of mapping: a method of documentation to deepen understanding of the world. But a collection of 40 million photographs is more powerful than a simple tool for virtual navigation.

How do pictures become maps?

This is where mapping meets its future. The translation step between the world we see and the world we’ve mapped disappears. With Mapillary, that map corresponds to the experiences of individuals.

Mapillary’s engineers are machine vision experts. Their passion is automating the gathering of information from pictures. In one image of a street, there are traffic signs, lane indicators and business addresses; all things that a modern map should include. There are also pieces that a map should not include: faces and license plates. With machine vision, personal data can be automatically and destructively blurred, while relevant data can be picked out and incorporated in maps without tedious hunting.

Text and sign recognition will be a huge boon to mapping. Street addresses can be picked out automatically, helping navigation achieve accuracy without tedious human effort. Freeway signs can be interpreted, speed limits can be included, and even stop signs and traffic lights can be labeled on maps. Businesses can be labeled automatically, with the hours of operation posted in the window and incorporated into the data of the map, which at this point has grown enormous. The increase in available computation power has prompted the development of these technological advancements, allowing our maps to hold more information than ever before.

Beyond the raw information, the physical buildings on a street are also in the picture. How do those make it onto a map?

Computer vision can reconstruct the buildings virtually in 3D. This can’t happen from a single photo, but as a car drives by, a camera could capture five or more pictures from different angles. If it’s centrally located, many Mapillary users could have documented separately, bringing the count up.

Mapillary’s technique is a tool called OpenSfM – short for open source structure from motion. Take the example of mapping a building: pictures from dozens of unique perspectives of the building are positioned relative to each other as machine vision stitches overlapping elements together. Next, a point on the building is identified in each picture; say the corner of a window. Understanding the perspective of each picture and then tracking the different positions of the window’s corner in each shot allows the computer to place the point in a 3D model. After a few thousand points have been analyzed, the building’s facade is built in 3D.

This feature can be explored on Mapillary using the point cloud feature in Mapillary’s street map. The 3D reconstruction allows the photos to blend together, with buildings in the distance moving seamlessly in the viewer. Closer, faster moving elements break up sometimes, showing the work still to come before the technology has reached its full potential.

This method isn’t accurate enough to replace LiDAR quite yet – but it will be eventually with more work from Mapillary’s engineers, and more data from Mapillary’s community. One day geo-tagged street-level pictures, supplemented with satellite images, will be fed to computers to build and update maps on a daily basis.

About the Author

Jan Erik Solem is the CEO of Mapillary and is passionate about all things computer vision related. Prior to co-founding Mapillary in 2013, he founded Polar Rose, a face recognition software for mobile and web, which Apple bought in 2010. Post acquisition, Solem worked as a computer vision team leader and researcher at Apple’s headquarters in Cupertino, CA. Solem is a WEF Technology Pioneer, has published over 15 patents and applications, and is the author of a best selling computer vision book called Programming Computer Vision with Python. Solem resides in Sweden and is an associate professor at Lund University.