California is eagerly expecting the bittersweet ending of another gruesome fire season in its second driest year on the record. Although less destructive than the 2020 fire season, the 2021 wildfire season will still be appallingly memorable for its large, destructive blazes.

For example, the Dixie fire is going down as the largest one in the state’s history – it burned nearly a million acres alone.

Will the 2021 fire season be the worst on record?

However, globally, the 2021 fire season has a good chance of becoming the worst one we have yet experienced.

Record forest fire-related emissions were noted in Siberia, with plumes spreading over the Northern Pole. The Greek island of Evia lost vast swathes of its iconic Mediterranean conifer forests and nearby homes, and Italy and Turkey were also ravaged during an exceptional heatwave in the Mediterranean. Moreover, the list is not nearly complete.

The Largest Tree in the World in Danger from Wildfires

Just when we thought that the unafflicted world had grown numb to the news of continuous burning, a striking image went viral worldwide.

It was a photograph of California firefighters putting protective blankets around the trunk of General Sherman – the largest tree in the world, around two and a half millennia old.

The ancient giant and its habitat, the Sequoia National Park, were in direct danger from the KNP Complex wildfire.

Are We at a New Geologic Chapter with Wildfires?

To fires, there are no borders, and nothing is sacred. There is only oxygen and fuel.

You have probably heard the term Anthropocene – a proposed geological epoch in which human influence has outgrown natural cycles and has a dominant role in shaping the circumstances on Earth.

Still, some people in the academic community say that the trends of Anthropocene are setting the stage for a new geologic chapter – Pyrocene, the age of fire.

What is more, some scientists believe that Anthropocene and Pyrocene are practically synonyms.

One of those people is the man who first coined the term.

How Fire Shaped Us – The Concept of Pyrocene

The term Pyrocene was first used in the essay “Fire Age” by Stephen J. Pyne*.

Pyne – both a scientist and a prolific writer – has built a solid narrative about fire as the dominant, propelling force that shaped the human civilization and the natural world it has occupied. In his writing, he painted a broad picture of human history with the discovery of fire ignition as its centerpiece.

Here are some crucial points of Fire Age:

- While the fire is a natural phenomenon, the very act of ignition is a rarity in the natural world. Pleistocene Hominids were the first creatures to control fire sparks, making ignition a frequent possibility – and did so universally. Wherever the ancient humans traveled, the fire had spread along with them.

- Human evolution was driven by our ability to use and control fire; it helped our ancestors cook food, dramatically impacting their physiology. The nutritional richness of cooked meals likely allowed us to have such large brains.

- Pyne suggests that making and manipulating fire is a human ecological signature – the unique way our species impact the environment. While some animals dig or knock down trees to modify their habitats, humans use fire for the same purpose. This ability to exert control of one’s surroundings had proven especially useful during the dawn of agriculture when intentional burnings have simultaneously cleared the landscape of unwanted vegetation and fertilized and prepared the soil for crops (many of which, interestingly, originated from fire-prone landscapes).

After millennia of rule by an open fire, further progress demanded more burning and more fuel than Earth’s surface biomass could offer. Thus, societies started to dig into the Earth’s crust to reach fossil fuels – coal, oil, and gas.

- The development of technology made societies repurpose ignition, turning from manipulating the open fire to manipulating combustion. If we summarize Pyne’s timeline, it becomes clear that the industrial revolution is marked by a shift – from the dominance of open fire to supremacy of combustion.

- In time, open fire has become a less prominent actor in human wellbeing and has increasingly started to be seen as a foe rather than an ally. This adversity to open fire has led to many landscapes and biomes becoming devoid of the much-needed fire by human intervention.

- On the other hand, our increasing ability to efficiently utilize combustion has led to a technological boom, and in turn, the boom required more and more fuel for burning. Pyne eloquently suggests that biodiversity is being replaced by pyrodiveristy – the machines running on combustion engines that are increasingly taking up space and resources that once belonged to the natural world.

Besides the direct destruction of natural ecosystems, burning through Earth’s geological layers had unforeseen consequences on Earth’s atmosphere – from air pollution to climate modification via massive release of carbon dioxide.

“Landscape flames are yielding to combustion in chambers, and controlled burns, to feral fires. The more we burn, the more the Earth evolves to accept still further burning. It’s a geologic inflection as powerful as the alignment of mountains, seas and planetary wobbles that tilted the Pliocene into the cycle of ice ages that defines the Pleistocene.” – Steven Pyne (Fire Age, 2015)

How Global Warming Makes Fires Worse

The frequent and harsh droughts and changing precipitation patterns cause high tree mortality and a general loss of vitality. That means that forests now harbor a lot of fuel – dry wood and branches and other dry plant material (which is also true for other ecosystems, such as Mediterranean shrub).

Dense conifer forests are additionally susceptible to fires because the resin has a high burning potential, and the dry pine needles form thick layers on the forest floor. And not only that – many conifer forests are sensitive to abnormally high temperatures and prolonged drought, making them susceptible to bark beetle attacks and, consequently, high tree mortality.

All these factors make them perfect for sprouting crown fires that go on to create regional megafires in the right circumstances.

The frequency of those “right circumstances” is increasing with global warming. The heat-boosted weather systems commonly bring long-lasting high winds that have the power to turn an average wildfire into a catastrophic one.

The change in the fire season pattern is also an evident consequence. Summer wildfire seasons are now, on average, 40 to 80 days longer than they were 30 years ago, and the Southwestern U.S.’ example suggests destructive fires now regularly occur outside of the official fire season.

In return, all the burning trees release carbon dioxide – and a lot of it. On September 21, Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS) announced that global emissions from wildfires for just two months – July and August 2021 – reached 2643.4 megatonnes, with main hotspots in North America, the Mediterranean, and Siberia.

As you may have already supposed – all the released carbon enhances the glasshouse effect and, consequently, global warming.

Surprising New Facts About Wildfires

One of the main impressions after getting introduced to the concept of Pyrocene is that fire is such an overpowering, all-encompassing environmental factor.

While the science of the past times had stripped fire of its mythical powers and credits, new research on wildfires and their influences seem to be bringing back the fire’s old, elemental glory.

It turns out that the range of wildfire influence is a lot broader than landscape destruction and direct danger to life.

The year 2021 has been very wild in terms of its wildfire season, but fire research has also been making some sparks.

Let us shed light on some of this years’ most intriguing wildfire discoveries.

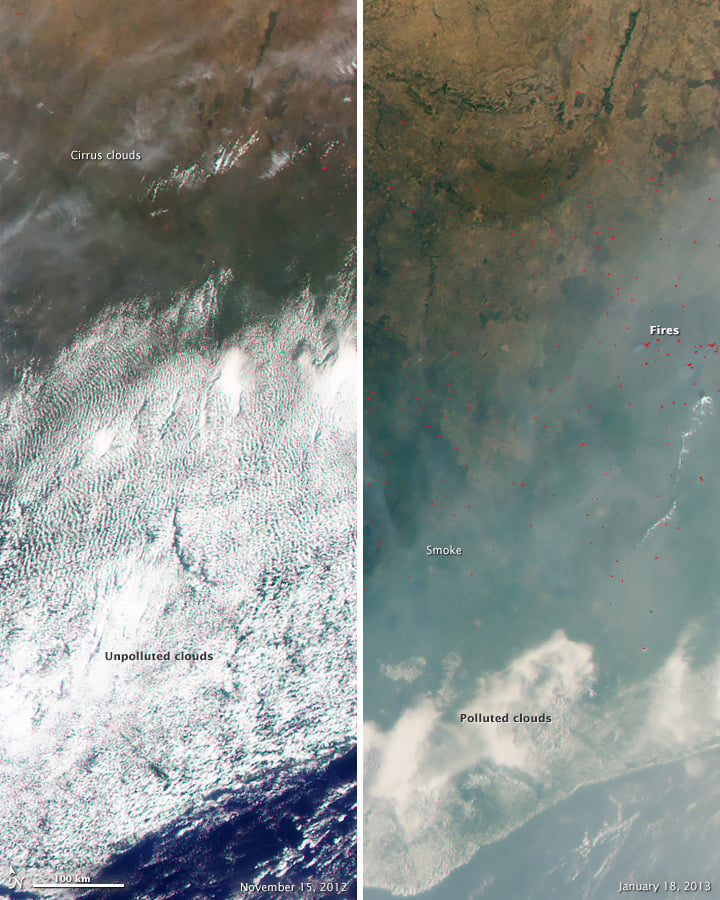

Clouds affected by wildfire smoke produce less or no rain

Rising smoke from wildfires inevitably saturates the clouds above with fire-generated particles. During the 2018 fire season, the researchers conducted a rare study on the consequences of the particle-cloud interaction. They analyzed data from small cumulus clouds affected by smoke during seven research flights.

What they found is that these clouds contained five times as many water droplets compared to the unaffected clouds – because all the fire-generated particles serve as nuclei for the formation of droplets.

However, more droplets didn’t make the clouds more likely to produce the rain – quite the opposite. The fire particle-generated droplets were only half as big as the droplets from control clouds, so they were less likely to bump into each other and merge, which would result in precipitation. In fact, the team concluded that the chances of rain from the studied clouds were “virtually zero.”

The findings of this study are in line with previous data from the Amazon, suggesting wildfires themselves lead to less precipitation, further increasing drought and wildfire risk.

Wildfires are creating their own weather systems

Wildfires can get so strong that thunderstorms form. The phenomena of fire-caused thunderstorms is known as pyroCbs, which is an abbreviation for pyrocumulonimbus clouds.

More: The Rise of pyroCbs

Wildfires are now conquering higher ground

Historically, higher elevations were thought to be not at risk of violent wildfires. However, new findings of an international study suggest that global warming allows wildfires to conquer higher ground.

The team analyzed the period between 1984 and 2017 and found that, in the West, the blazes were moving upwards at the rate of 25 feet (7.6 meters) per year.

There are several reasons behind this advancement of wildfires towards higher elevations. Warmer temperatures, earlier snowmelts, and the increased influx of dry air make the mountainsides drier and, thus, more prone to catching fire.

Australian 2019-2020 fires released much more carbon than thought – and caused a major phytoplankton bloom

One of the worst fire seasons in Australia that struck the continent’s east coast two years ago had an even greater impact than previously thought.

From September 2019 to March 2020, the bushfires affected 46 million acres (72,000 square miles), killing 34 people and over 1 billion animals. Also, it turns out they released twice more carbon dioxide than previously thought.

The team led by Ivar R. van der Velde from SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research calculated that the fires released from 517 trillion to 867 trillion grams of carbon dioxide. He added that “emissions from this single event were significantly higher than what all Australians normally emit with the combustion of fossil fuels in an entire year.”

What was also discovered by another study is that immense clouds of smoke and ash that traveled all the way to the Southern Ocean caused a widespread and massive phytoplankton boom by saturating the ocean water with nutrients.

Tracking this bloom’s dynamics has added to the knowledge of the effect of bushfires in Australia and has helped us learn how they relate to marine ecosystems and their nutrient cycles.

Fighting Every Fire Likely Contributed To Megafires

Towards the end of Fire Age, Pyne mentions the fading significance of small, sporadic natural fires and prescribed burnings, suggesting they need to be seen for what they are – a potential ally in landscape management. That is the topic that often runs through his work writings – and with a good reason.

As megafires and prolonged seasons become the new normal, more people are re-thinking our fire management strategies – and writing about it.

Forests of Western U.S. are naturally prone to fires – and always have been. Lighting strikes and Indigenous controlled burning created patchwork-style landscapes, with ecosystems in different phases of ecological succession. The tribes purposefully regenerated shrublands and grasslands that sustained them by using fire.

What is perhaps even more critical in terms of forest management is that these small-scale fires would spend much of the available fuel and break the landscape’s uniformity.

Modern zero-tolerance of fires, hand-in-hand with forestry practices intended to maximize wood production, created what Pyne called “a tinderbox” in the American Southwest. As he points out: “Over time, the belief in the intrinsic evil of free-burning flame also yielded to the realization that the removal of fire, like that of the wolf, could unravel whole ecosystems.”

While finding the best strategy for genuinely sustainable wildfire management remains a challenge, the need for adaptive forest management to increase resilience both to wildfires and climate change is evident in 2021. As it turns out, the notion of fighting fire with fire might not be so contradictory after all.

Conclusion

Whether you consider Pyrocene a geological fact or a philosophical construct, it is undeniable that anthropogenic fire and combustion have shaped the Earth we know today.

Ideas about how fire shaped us, proposed by professor Pyne, are not shocking. Still, their absence from daily thinking proves how fundamental firepower is to our identity.

We are so accustomed to handling fire that we do not see our power of controlling it as an oddity – and it is one.

Ironically, our overuse of combustion is now making that power slip away from us. It is certain that the violent wildfires are here to stay and will make themselves known – with increasing force.

Like our ancestors once mastered the use of flames to push back against the often-hostile environment, we will have to learn to handle our future blazes in novel ways – those that spur perseverance and harmony rather than annihilation.

*Stephen J. Pyne is an emeritus professor at Arizona State University, specializing in environmental history, the history of exploration, with a focus on the history of fire. He has authored over 30 books on the topic, including Fire: A Brief History (University of Washington Press, 2001), and has just recently published The Pyrocene (University of California Press, 2021).

References

The Studies:

Alizadeh, M.R., et al. (2021) Warming enabled upslope advance in western U.S. forest fires. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118 (22), e2009717118.

Pyne, Stephen. (2017). Big Fire; or, Introducing the Pyrocene. Fire. 1. 1. 10.3390/fire1010001. https://hdl.handle.net/2286/R.I.46147

Tang, W., et al. Widespread phytoplankton blooms triggered by 2019–2020 Australian wildfires. Nature 597, 370–375 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03805-8

Twohy, C. H., et al. (2021). Biomass burning smoke and its influence on clouds over the western U. S. Geophysical Research Letters, 48, e2021GL094224. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GL094224

van der Velde, I.R., van der Werf, G.R., Houweling, S. et al. Vast CO2 release from Australian fires in 2019–2020 constrained by satellite. Nature 597, 366–369 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03712-y

Articles:

Bryner, Jeanna. Dixie Fire becomes largest in California history. Live Science. 7 August 2021 https://www.livescience.com/dixie-fire-largest-california-wildfire.html

Climate Change Pushes Fires to Higher Ground, Nasa Earth Observatory https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/148789/climate-change-pushes-fires-to-higher-ground

Copernicus: A summer of wildfires saw devastation and record emissions around the Northern Hemisphere. Copernicus EU. 21 September 2021 https://atmosphere.copernicus.eu/copernicus-summer-wildfires-saw-devastation-and-record-emissions-around-northern-hemisphere

Voiland, Adam. More Smoke Can Mean Less Rain. NASA Earth Observatory. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/86672/more-smoke-can-mean-less-rain

Miranda, Gabriela. General Sherman, the world’s largest tree, is wrapped in fire-resistant blanket as wildfires threaten park. USA Today. 17 September 2021 https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2021/09/17/worlds-largest-tree-wrapped-aluminum-blanket-wildfire-arrives/8376844002/

Mott, Nicholas. What Makes Us Human? Cooking, Study Says. National Geographic News. 27 October 2012. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/121026-human-cooking-evolution-raw-food-health-science

Prichard, Susan J.; Hagmann, Keala; Hessburg, Paul. How years of fighting every wildfire helped fuel the Western megafires of today. The Conversation. 2 August 2021 https://theconversation.com/how-years-of-fighting-every-wildfire-helped-fuel-the-western-megafires-of-today-163165

Pultarova, Tereza. The devastating wildfires of 2021 are breaking records and satellites are tracking it all. Space.com 11 August 2021 https://www.space.com/2021-record-wildfire-season-from-space

Pyne, Stephen. Burning Like A Mountain. Aeon. 14 January 2014 https://aeon.co/essays/how-the-american-southwest-became-a-tinderbox

Pyne, Stephen. The Fire Age. Aeon. 5 May 2015 https://aeon.co/essays/how-humans-made-fire-and-fire-made-us-human

Satellite Data Record Shows Climate Change’s Impact on Fires. Ellen Gray, NASA’s Earth Science News Team. NASA Global Climate Change 10 September 2019 https://climate.nasa.gov/news/2912/satellite-data-record-shows-climate-changes-impact-on-fires

Schweizer, Deb: Wildfires in All Seasons? USDA Forest Service, Fire Aviation and Management in Forestry. July 2021 https://www.usda.gov/media/blog/2019/06/27/wildfires-all-seasons

The General Sherman Tree National Parks Service, Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks California https://www.nps.gov/seki/learn/nature/sherman.htm

Related

- 2021 Wildfires in the U.S. and Canada

- Climate Change is Increasing Post-Wildfire Landslides in Southern California

- Three of Colorado’s Wildfires are the Largest in Recorded History for the State

- Carbon Monoxide from the California Wildfires

- How Wildfires are Changing Boreal Forests and Increasing Emissions